In 2010 I read a book that marked the beginning of what I might term my true musical awakening. It was not something from music history or theory. Not even Quantz! It was the book Bounce by Matthew Syed, an Olympic-champion table tennis player. The book explores the neuroscience behind human achievement, and I cannot possibly recommend it highly enough. It was this book that started me on the road to codifying my ideas about musicianship and practice. The final golden rule, discussed below, was one of the first of these developed ideas.

Around the same time I read Bounce, I had begun to wonder how I could help my private students improve more effectively. Their progress in lessons was great, but they often seemed to stall between our sessions. This led me to believe that there was something in the way my students were practicing that wasn't helping them attain lasting improvement. This hypothesis resulted in what I call the "practicing lesson," a tool I still use today.

In a practicing lesson, I would take 40-50% of the lesson time to watch a student practice and make notes of good and bad habits that impacted their learning. In the remainder of the lesson, I walked them through an alternative practice session, highlighting good habits and correcting bad habits. The real lesson for me, as the teacher, was the degree to which my students needed these sessions, given how little they seemed to know about practicing. And why should they know anything about practicing? No one, including me, had taught them how to practice! TEACHER FAIL.

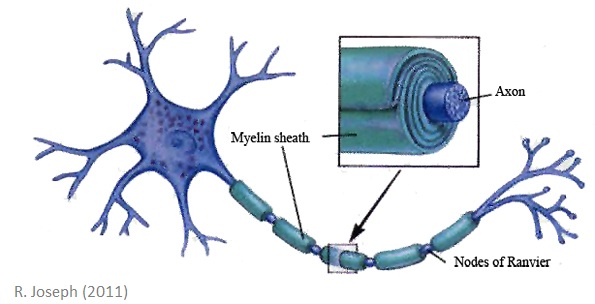

In short, my students truly believed that any and all time spent at home with flute in hand = practicing. However, as every pro knows, this is not the case, as vividly stated by Syed in Bounce, building upon the writings of Malcolm Gladwell: "Purposeful practice also builds new neural connections, increases the size of specific sections of the brain, and enables the expert to co-opt new areas of gray matter in the quest to improve.... We can now see that the very process of building knowledge transforms the hardware in which the knowledge is stored and operated.... You can purchase access to this prime neural real estate only by building up a bank deposit of thousands of hours of purposeful practice. That, if you like, is the price of excellence."

Around the same time I read Bounce, I had begun to wonder how I could help my private students improve more effectively. Their progress in lessons was great, but they often seemed to stall between our sessions. This led me to believe that there was something in the way my students were practicing that wasn't helping them attain lasting improvement. This hypothesis resulted in what I call the "practicing lesson," a tool I still use today.

In a practicing lesson, I would take 40-50% of the lesson time to watch a student practice and make notes of good and bad habits that impacted their learning. In the remainder of the lesson, I walked them through an alternative practice session, highlighting good habits and correcting bad habits. The real lesson for me, as the teacher, was the degree to which my students needed these sessions, given how little they seemed to know about practicing. And why should they know anything about practicing? No one, including me, had taught them how to practice! TEACHER FAIL.

In short, my students truly believed that any and all time spent at home with flute in hand = practicing. However, as every pro knows, this is not the case, as vividly stated by Syed in Bounce, building upon the writings of Malcolm Gladwell: "Purposeful practice also builds new neural connections, increases the size of specific sections of the brain, and enables the expert to co-opt new areas of gray matter in the quest to improve.... We can now see that the very process of building knowledge transforms the hardware in which the knowledge is stored and operated.... You can purchase access to this prime neural real estate only by building up a bank deposit of thousands of hours of purposeful practice. That, if you like, is the price of excellence."

Common core for music teachers?

Common core for music teachers? It was the "purposeful" part that was missing from my students' practicing. Instead of giving their practice purpose by systematically addressing and fixing problems/mistakes (as I discuss at length in The Scientific Method of Practicing), students were either playing through problematic passages repeatedly, hoping the problems would fix themselves (violating Golden Rule #1 of Practicing) or worse, playing through exercises, etudes, pieces, etc., and ignoring problems altogether (which, when done repeatedly, breaks Golden Rule #4 of Practicing).

This led to a simple maxim, which I gave to my students and which has now become the final Golden Rule.

Golden Rule #5 of Practicing: Playing is not practicing.

I love that what we do as musicians is generally referred to as "play." This descriptor directly recalls the sense of joy I presume we have all felt when we have made music, and we should set aside time with our instruments simply to play and explore, when the only purpose is enjoyment. As essential as it is, however, this act in no way approximates the painstaking process of setting and achieving goals that is practice. While playing and practicing are well worth our time, for those of us willing to pay Syed's "price of excellence," more of our temporal currency must be spent on practicing.

As I tell my students, "Practicing might not be as fun as playing, but do you know what is fun? BEING A TOTAL BOSS ON YOUR INSTRUMENT. And that's what happens when you bank enough hours practicing."

With that, let the church say, "Amen." Happy Holidays!

-------------------

If you want info like this regularly, subscribe to Dr. Tim's Teaching Tips on the right! I promise you'll only be emailed with new blog posts, never spam. You can also add the blog to your RSS feed.

Need a boost in your practicing? I am now available for practicing lessons in person in Dallas and online via Skype! Contact me for information and rates.

Finally, if you like this post, then you'll love The Scientific Method of Practicing, where the underlying information is covered in detail. Head over to the publications page to pick up a copy.

This led to a simple maxim, which I gave to my students and which has now become the final Golden Rule.

Golden Rule #5 of Practicing: Playing is not practicing.

I love that what we do as musicians is generally referred to as "play." This descriptor directly recalls the sense of joy I presume we have all felt when we have made music, and we should set aside time with our instruments simply to play and explore, when the only purpose is enjoyment. As essential as it is, however, this act in no way approximates the painstaking process of setting and achieving goals that is practice. While playing and practicing are well worth our time, for those of us willing to pay Syed's "price of excellence," more of our temporal currency must be spent on practicing.

As I tell my students, "Practicing might not be as fun as playing, but do you know what is fun? BEING A TOTAL BOSS ON YOUR INSTRUMENT. And that's what happens when you bank enough hours practicing."

With that, let the church say, "Amen." Happy Holidays!

-------------------

If you want info like this regularly, subscribe to Dr. Tim's Teaching Tips on the right! I promise you'll only be emailed with new blog posts, never spam. You can also add the blog to your RSS feed.

Need a boost in your practicing? I am now available for practicing lessons in person in Dallas and online via Skype! Contact me for information and rates.

Finally, if you like this post, then you'll love The Scientific Method of Practicing, where the underlying information is covered in detail. Head over to the publications page to pick up a copy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed