"Perfect practice makes perfect." Or "If you never make a mistake, you'll never make a mistake." Thus spaketh many great musicians and teachers, past and present. And while I am a proponent of making friends with mistakes, as I discussed briefly last week and write about at some length in The Scientific Method of Practicing, there is a central kernel of truth in these epigrams. While actively trying to avoid mistakes is itself to be avoided, it is perhaps worse to repeat them (see Golden Rule #1 of Practicing). Ergo, the next golden rule, a corollary of Rule #1:

Golden Rule of Practicing #4: Repeat, repeat, repeat, repeat, repeat--but only when it's right.

Repetition has a hallowed place in the practice of effective musicians (as well as artists of any stripe, scientists, mathematicians, historians, etc.). Dr. Robert Duke, Head of Music and Human Learning at The University of Texas at Austin, writes about this from a psychological point of view in his excellent book, Intelligent Music Teaching: "Repetition is the mechanism through which habit strength develops. The more often we repeat a given behavior, the more that behavior becomes a part of what we do."

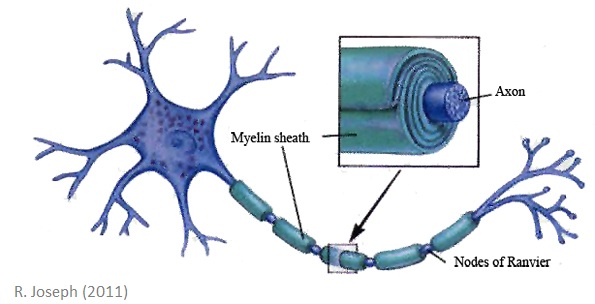

This statement is so true that it plays out on a biological level in our brains, thanks to a material called myelin. Daniel Coyle writes about this phenomenon in his influential book, The Talent Code: "Every human skill...is created by chains of nerve fibers carrying a tiny electrical impulse.... [The neural insulator] myelin's vital role is to wrap those nerve fibers the same way that rubber insulation wraps a copper wire, making the signal stronger and faster.... When we fire our circuits in the right way--when we practice swinging that bat or playing that note--our myelin responds by wrapping layers of insulation around that neural circuit, each new layer adding a bit more skill and speed. The thicker the myelin gets, the better it insulates, and the faster and more accurate our movements and thoughts become."

Golden Rule of Practicing #4: Repeat, repeat, repeat, repeat, repeat--but only when it's right.

Repetition has a hallowed place in the practice of effective musicians (as well as artists of any stripe, scientists, mathematicians, historians, etc.). Dr. Robert Duke, Head of Music and Human Learning at The University of Texas at Austin, writes about this from a psychological point of view in his excellent book, Intelligent Music Teaching: "Repetition is the mechanism through which habit strength develops. The more often we repeat a given behavior, the more that behavior becomes a part of what we do."

This statement is so true that it plays out on a biological level in our brains, thanks to a material called myelin. Daniel Coyle writes about this phenomenon in his influential book, The Talent Code: "Every human skill...is created by chains of nerve fibers carrying a tiny electrical impulse.... [The neural insulator] myelin's vital role is to wrap those nerve fibers the same way that rubber insulation wraps a copper wire, making the signal stronger and faster.... When we fire our circuits in the right way--when we practice swinging that bat or playing that note--our myelin responds by wrapping layers of insulation around that neural circuit, each new layer adding a bit more skill and speed. The thicker the myelin gets, the better it insulates, and the faster and more accurate our movements and thoughts become."

In other words, Dr. Duke could just as well have said that what we do repeatedly becomes part of us, so it is important that we repeat what we want to be and don't repeat what we don't want to be. If we want to be great musicians, we have to play great, repeatedly. However, it is impossible to do that without embracing and processing our problems. In certain circumstances, as Noa Kageyama cites in his indispensable blog, The Bulletproof Musician, this process can be jump started by--gasp!--purposely exaggerating our mistakes.

Once we truly understand our problems, we can begin to choose to play differently, to play better, and that's the choice we should make over and over, starting on the scale of the individual problem. We should play any formerly problematic passage well, repeatedly, immediately after fixing it.

How much is repeatedly? Some teachers say five times in a row; others say seven or ten. I like to go for broke and set the bar at 15-20 times, allowing for one or two outliers. However, out of 15-20 attempts, if more than one or two go astray, I consider the problem not to be fixed after all and set about solving it again. After all, as Dave Booth commented on my Golden Rule #1 of Practicing, from his teacher Rupert Neary: "If you play it wrong once, remember that, and don't do it again. But if you forget, and play it wrong twice, mark it, because if you play it wrong three times, you are practicing it."

-------------------

If you want info like this regularly, subscribe to Dr. Tim's Teaching Tips on the right! I promise you'll only be emailed with new blog posts, never spam. You can also add the blog to your RSS feed.

Finally, if you like this post, then you'll love The Scientific Method of Practicing, where the underlying information is covered in detail. Head over to the publications page to pick up a copy.

Once we truly understand our problems, we can begin to choose to play differently, to play better, and that's the choice we should make over and over, starting on the scale of the individual problem. We should play any formerly problematic passage well, repeatedly, immediately after fixing it.

How much is repeatedly? Some teachers say five times in a row; others say seven or ten. I like to go for broke and set the bar at 15-20 times, allowing for one or two outliers. However, out of 15-20 attempts, if more than one or two go astray, I consider the problem not to be fixed after all and set about solving it again. After all, as Dave Booth commented on my Golden Rule #1 of Practicing, from his teacher Rupert Neary: "If you play it wrong once, remember that, and don't do it again. But if you forget, and play it wrong twice, mark it, because if you play it wrong three times, you are practicing it."

-------------------

If you want info like this regularly, subscribe to Dr. Tim's Teaching Tips on the right! I promise you'll only be emailed with new blog posts, never spam. You can also add the blog to your RSS feed.

Finally, if you like this post, then you'll love The Scientific Method of Practicing, where the underlying information is covered in detail. Head over to the publications page to pick up a copy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed